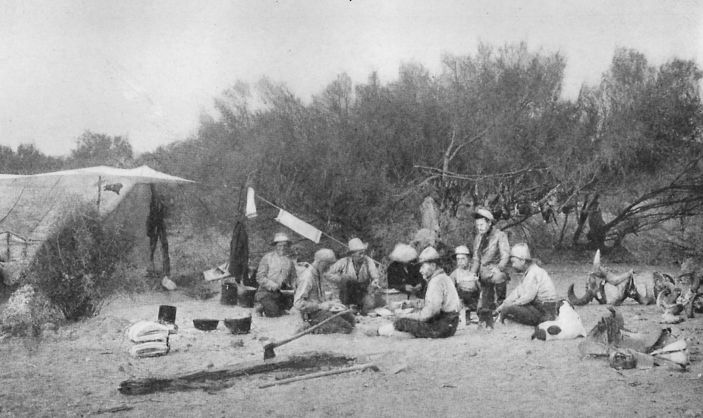

The Tumamoc stalwarts at their campfire in November 1907

as they progressed on their expedition in NW Mexico.

W.T.Hornaday 1908 — "Camp-fires on desert and lava"

New York (Charles Scribner's Sons)

books.google.com/books?id=B_AOAAAAYAAJ

The Tumamoc stalwarts at their campfire in November 1907 |

A century ago, William Hornaday, director of The New York Zoological Society, a good friend of Daniel MacDougal and one of the nation's most famous and respected animal conservationists, decided to organize a camping trip to "conserve" the desert bighorn sheep. But he had a funny way of showing his intentions. First, he hunted and shot the species he wished to conserve. Then he displayed them as trophies to encourage interest and support. Ah, well, it was a different time.

Hornaday arrived in Tucson in November, 1907. Ostensibly he would settle the issue of which species the desert bighorn sheep belonged to, but you can tell from the book he wrote about the adventure that he was just looking for a good excuse for a hunting and camping trip with his buddies, Daniel MacDougal, Carnegie Lab director, and John Phillips, sportsman and photographer from Pittsburgh, who had accompanied him on a previous trip to British Columbia.

Their quarry, the sheep, lived in the region of the Pinacate Mountains — a searing, dry, desolate, dangerous, lava-strewn area of Old Mexico south of the Arizona border that Hornaday describes thus: "No photograph ever can convey ... the savage grandeur and the scowling terrors of (the Pinacate lava). It was like Dante's Inferno on the half shell." Six others went along including our hero, Godfrey Sykes, who was officially designated Geographer to the expedition.

Let me bring you three scenes from the trip in the words of the very men involved. They are great fun to read, especially the pompous purple prose of Hornaday himself. They will absolutely convince you that our Mr. Sykes was a perfectly remarkable man — in Phillips's own words, "a man of iron" and, in Hornaday's, "invincible." And besides, the prose is now in the public domain. (Unless marked otherwise, Hornaday wrote it.)

The fifteenth of November was one of the great days of the trip... It was Mr. Phillips and Mr. Sykes who scored heaviest on that day. They returned through the darkness very shortly after the Doctor and I arrived, tired but triumphant. Mr. Sykes had two splendid new craters to his credit and Mr. Philips had collected two lava rams. Of the latter, one was an Old Residenter, with magnificent horns...

Mr. Sykes was fairly bursting with enthusiasm over the craters and the sheep, but Mr. Phillip's chief excitement was due to the astounding manner in which Mr. Sykes had put a hundred and fifty pounds of mountainsheep ram on his back and carried it a mile down a terrible mountain side of rough lava garnished with choyas... I never knew any feat of arms — or of legs — to so arouse John M. as did that; but when I saw that mountain side, a few hours later, I fully understood...

(John M. Phillips tells the tale:) "The leader of the band was standing on the lava ridge across the head of that cañon, on that pinnacle of red lava, outlined against the sky. At the base of the pinnacle, one to the right and two to the left, I could see the heads of the other rams, all looking directly at me.

"Just as I dropped on my knee to shoot, the setting sun broke through the clouds behind me, gloriously bringing out all the details. The leader was standing almost broadside to me, his massive head accentuated by the deer-like leanness of his neck and body. The shining sun and the falling rain had formed a rainbow directly back of the pinnacle on which the ram stood. ... That magnificent ram, standing like a statue on the pedestal of red bronze lava, washed by the falling rain and lit up by the setting sun; on one side a head with horns quite as massive as those of the central figure, on the other the heads of two younger rams, and the whole group overarched by a gorgeous rainbow! Estimating the distance at three hundred yards, I held slightly over the shoulder of the big ram, and the big ball struck him fair in the heart. His legs doubled under him like a jackknife and he slid off the pinnacle. Striking the rough lava, he turned over twice and then lay still, while his friends, after staring at me a few seconds, disappeared like shadows.

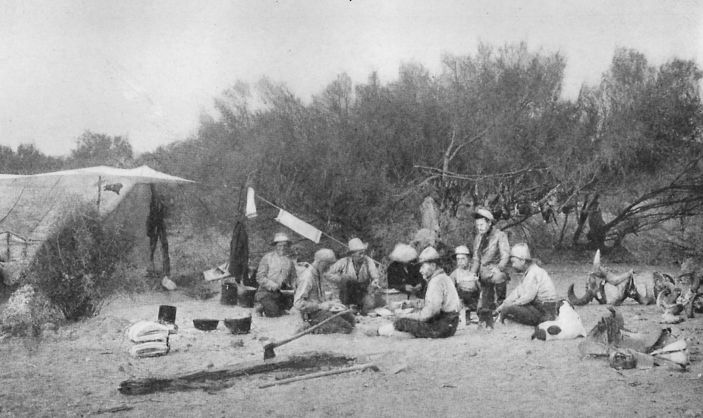

"... I turned back and picked my way over the fissures and broken lava, feeling like a vandal who had destroyed a beautiful statue, ...(w)hen Sykes joined me where the big ram lay. ... I then photographed Mr. Sykes with the ram, and, as I told him the story of the rainbow, he became 'powerful sorrowful.'

Mr. Sykes examines the bighorn ram killed minutes before by John Phillips

Photo by John M. Phillips, 15 November 1907

"By the time we had removed the entrails ... it was quite dark; and then Mr. Sykes and I almost had a row. It was my opinion that a hind-quarter would be sufficient for camp-meat, and that we could as well get the remainder later on. Sykes declared that having been out of meat for a long time, and not having tasted any mountain mutton for years, he was equal to a hind-quarter himself. He asked whether I thought we were hunting worms for a nest of young robins or trying to supply meat for a lot of starving land pirates?

We were on the side of a high and very steep mountain of red lava that was liberally garnished with Bigelow choyas — the meanest of the mean. A false step would have meant a fall of perhaps ten or twenty feet on lava blocks that would cut like knives... The lava was terrible, but the awful choyas that were so generously sprinkled over it were the crowning insult. Their millions of white, hornlike spines glistened ... but the thought of stumbling and falling upon one of them gave me chills.

Cylindropuntia Bigelovii — teddybear cholla.

Photo by T. Beth Kinsey, fireflyforest.com

"I didn't think he would get very far with the hundred-and-fifty-pound body of that sheep, but in order not to be out-done, I concluded to pack in the head. Sykes swung the carcass to his shoulder and down into those black lava fissures, garnished with that devilish choya, we went...

"Loaded down as I was with my gun, my camera and the head of the sheep, the irregular chunks of lava, like fragments broken from a large mass of glass, punished my feet severely. On that steep mountain side the footing was so uncertain that I was afraid of falling and landing on a choya, and perhaps putting out an eye. I felt very sorry for Mr. Sykes and was afraid he would fall and hurt himself; so after going some little distance I checked up and begged him to throw down his burden until the morning. But that man of iron appeared to be tickled to death with his load of meat, and held onto it like an English bulldog.

"Two or three times in that terrible descent I checked up and begged him to throw down the sheep and rest; but he replied that it would get full of choya spines, and that a porcupine would not be a nice thing to carry. Finally I lost him.

"Returning, I found him extracting, without even swearing, a lot of choya spines that the dangling legs of the sheep had driven against him. Again forced along without rest by that relentless man of iron, self pity made me hope that he would have to give up his task, and would then assist me in bearing my burdens, which at every step seemed to be getting unbearably heavy and more difficult to carry.

"Finally, after going about a mile we (reached camp)... in the dark."

That night we feasted on mountain-sheep steaks that were young and tender; and everybody gormandized except me.

The next morning, early and brightly, we set out for the craters (three and a half miles away)...

First we went to the crater which the Boys said was "shaped like a cloverleaf." ... As in honour bound, Mr. Sykes climbed down into that crater to measure it. He found it to be two hundred and fifty feet deep, one thousand five hundred feet wide at the bottom, and its rim was nearly a mile in circumference.

But in craters, the Wonder of wonders was reserved for the last. ... I thought that the descriptions of the two excitable members had prepared my mind for the Sykes Crater, and that I could take it quite calmly; but I was wrong on both counts. ...You seem to stand at the Gateway to the Hereafter. The hole in the earth is so vast, and its bottom is so far away, it looks as if it might go down to the centre of the earth. The walls go down so straight and so smooth that at one point only can man or mountain sheep descend or climb out. There the roughness of the rocks renders it possible for a bold and nerveless mountaineer to make the trip.

Sykes Crater, Pinacate Wilderness, NW Sonora, Mexico

Photo by MacDougal

Of course Mr. Sykes went down, bearing his aneroid and pedometer. The depth of it, from rim to bottom, he found to be 750 feet, and the inside diameter, at the bottom, was 1,400 feet. The bottom is about 150 feet above sea level.

In summing up the evidence he said, "How far do you think it is around this rim?"

I thought "a mile and a half"; but to keep from being surprised I said,

"Two miles." And he said,

"It is very nearly three!"

...We lingered long on that breezy rim, gazing spell-bound into the abyss, and at the red lava peaks looming up high above the rim on both the east and the west.

Naturally, we speculated much on the proposed trip across the sand-hills to the waters of the Gulf of California. At first we all intended to make the trip. But... a hot and tiresome tramp through ten miles of loose sand, to a muddy old foreshore with nothing upon it, was too much...

But the Doctor protested that he did want to see the botanical features of those sand-hills; and Mr. Phillips vowed that he must have a bath in the Gulf. Mr. Sykes said, "Well, I simply must go, to test my aneroid at sea level, in order to get my elevations correct. For me, there really is no option."

In the end, the Geographer was the only man who went...

One night, at tea-time, Mr. Sykes was totally missing. No one had seen him since morning, when he was observed running loose on the lava field toward the west, dragging his lariat. When late bedtime (eight o'clock) came without bringing him, some Wise One exclaimed, "I'll bet anything he's gone to the Gulf!"

And sure enough, he had! About one o'clock that afternoon, while wandering over the lava, mapping and measuring peaks, he said to himself, in genuine English style, "It's a fine day; I'll go to the Gulf this afternoon!"

Without further parley, or a word to any one, off he started. He tramped that whole round trip... in about thirteen hours. It was about half-past one in the morning when he jauntily tramped up to camp, helped himself to some fragments of cooked food that the rest of us had carelessly overlooked, and slipped into his sleeping-bag.

The next morning he rose with the rest of us, as lively and debonair as any of us, and quite as ready for the doings of the day. This is what he told us about his trip ...

"When I left camp yesterday morning, I went over to the big lava butte to the west, climbed it and took a lot of sights, and then, as it was still early, I thought I would go down to sea level with my aneroid, so as to get a check on my readings on Pinacate. From the top of my butte I picked out what looked to be a fairly easy route across the sand-hills, set my pedometer and started. ... I estimated my distance from the shore-line to be from fifteen to twenty miles, and this proved to be fairly correct; for from the time of leaving the top of the butte until I got back into camp, my pedometer tallied forty-three miles.

"The sand-hills averaged about five miles across, and in them the walking is very bad. The Gulf front of these hills is a clear-cut line, and the highest dunes are close to this eastern edge.

"Once through the sand, my course lay straight across some galleta grass flats toward some bare-looking saladas that I could see from the tops of the dunes. The walking was now very good, and by sundown I was probably two-thirds of the way from the sand to the shore. The full moon rose over Pinacate about dusk, and so I had plenty of light.

"I soon reached the tide flats, got down as far as salt water, corrected the scale of my aneroid and started back to camp. I had determined to make, on my way back, a detour toward the south, through the sand-hills, as my last sight in that direction from the frontal dune had shown me a better route than the one I had followed in going toward the shore.

"I got through without any difficulty, steering by the ten stars, and as I had a latch-key to my own particular sleeping-rock at the Tule Tanks, I knew that none of you would be sitting up waiting for me. I must say, however, that you all had disgustingly hearty appetites at supper, for there was mighty little left to eat."

(And, by the way, we know he actually made that trek — 43 miles in about 13 hours after a full morning's work — because...

he came back with specimens of various species of seashells! MLRo)

—— To contents —— To top