Meet Tumamoc's Pioneers & Heroes

Frederick Coville

Volney Spalding

Daniel MacDougal

William Cannon

Burton Livingston

Godfrey Sykes

Francis Lloyd

Burt Bovee

Forrest Shreve

Effie Spalding

Ray Turner

Paul Martin

| |

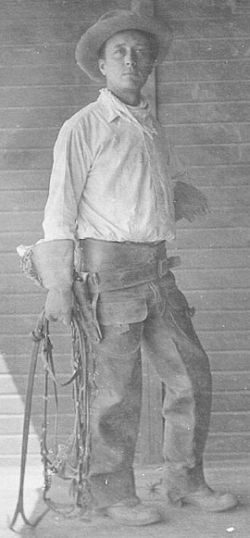

Lloydie in Zacatecas, 1907. |

Born 4 October, 1868 in Manchester, England, Lloyd's teaching career began in 1901 at Williams College. Then he was instructor in biology and geology at Pacific University (Oregon). He returned to the eastern US to accept a position with the Teacher's College of Columbia University. While there, he wrote his first book (with co-author Bigelow), a book on the teaching of biology. In the summer of 1904, Lloydie (for that is what his grandchildren call him to this very day) visited Tumamoc supported by a very small research grant from the Botanical Society of America. He came to the desert to take up the question of how plants control their breathing. Botanists all knew that the leaves of plants are full of tiny holes called stomata (the Greek word for mouths). Through these holes, carbon dioxide enters and oxygen leaves the plant. They must have the carbon dioxide for synthesis of sugar, but while their stomata are open, they are also losing precious water — a serious cost in a desert. How do they control those openings? Do desert plants have any special tricks or structures to do it? It was a huge question but despite the shortness of his visit, Lloyd was undaunted. In fact, he did get a good start. Lloyd returned to Tumamoc in the summer of 1905, to continue his studies, this time with a $500 grant from the Carnegie Institution itself. But there was still more question than time for a complete answer. However Lloyd's work was progressing so nicely that Director Daniel MacDougal offered him a position at the Desert Lab so that he could complete it. In 1906, he resigned from Columbia University and made the move. |

|

Wait a second! MacDougal forgot to tell Lloydie that there was only enough money for a six-month appointment! To this day, Lloydie's descendants remember that heartless treachery. The very idea of luring a man with a pregnant wife away from a secure faculty position at an Ivy League school to a tent village at the foot of a remote desert hill, knowing that he'd be out on his ear after six months! Nevertheless those six months turned out to be enough. Before his stay was over, Lloyd had cracked the problem, a story you will find on another page of this web site. It's essence: The opening of each stoma is controlled by a pair of odd-shaped cells called guard cells. Starch in the guard cells rises and falls every day. The more starch, the stiffer the walls of the stoma and the more it opens. The starch tends to peak at about sunrise each morning. Then it rapidly disappears, especially on a warm day; the stomatal pores get very tiny and very little water escapes from the plant. (1908, The Physiology of Stomata, Publication 82 of The Carnegie Institution of Washington) Time and modern methods have refined what we know about stomata. But Francis Lloyd's explanation still stands after more than 100 years. Despite the very short time he spent at Tumamoc, Lloyd's discovery is one of the lab's most significant. After Tumamoc, Lloyd studied a small Mexican rubber plant in Zacatecas. The company that hired him hoped to find out how our continent could produce its own rubber. In those days rubber played a role in America like petroleum does today. He remained a consultant to this company right through WWII. Leaving Mexico in 1909, he became a professor at Alabama Polytechnic Institute (now Auburn University), and then in 1912 accepted the very distinguished Macdonald Professorship of Botany at McGill University, a chair he held until retiring in 1934. His time at McGill brought many honors including the Presidency of the Royal Society of Canada. And he also conducted the most popular research of his career, studies of carnivorous plants (completed in 1942, The Carnivorous Plants, Chronica Botanica http://dx.doi.org/10.5962/bhl.title.5965). We need not be surprised. Carnivorous plants have traps that they use to capture animal food. Open. Close. Just like stomata! Lloyd found out how they worked. He pioneered the use of motion pictures in science, documenting the functioning of those intricate little traps. And his book opens the fascinating question of their repeated evolution because, you see, carnivorous plants have evolved many times in many unrelated sorts of plants. Francis Ernest Lloyd died at his home in Carmel, California, on 10 October, 1947. | |